III) Geological Event

Turbidity currents, which create turbidite deposits, occur on time scales ranging from minutes to days. In contrast, in any location, the time between successive depositional events is though to be on order of years to thousand years. Therefore, when studying turbidite deposits, geoscientists are dealing with intermittent, punctuated equilibrium events. So, before going on, it is important to, quickly, review the meaning and timing duration of a geological event.

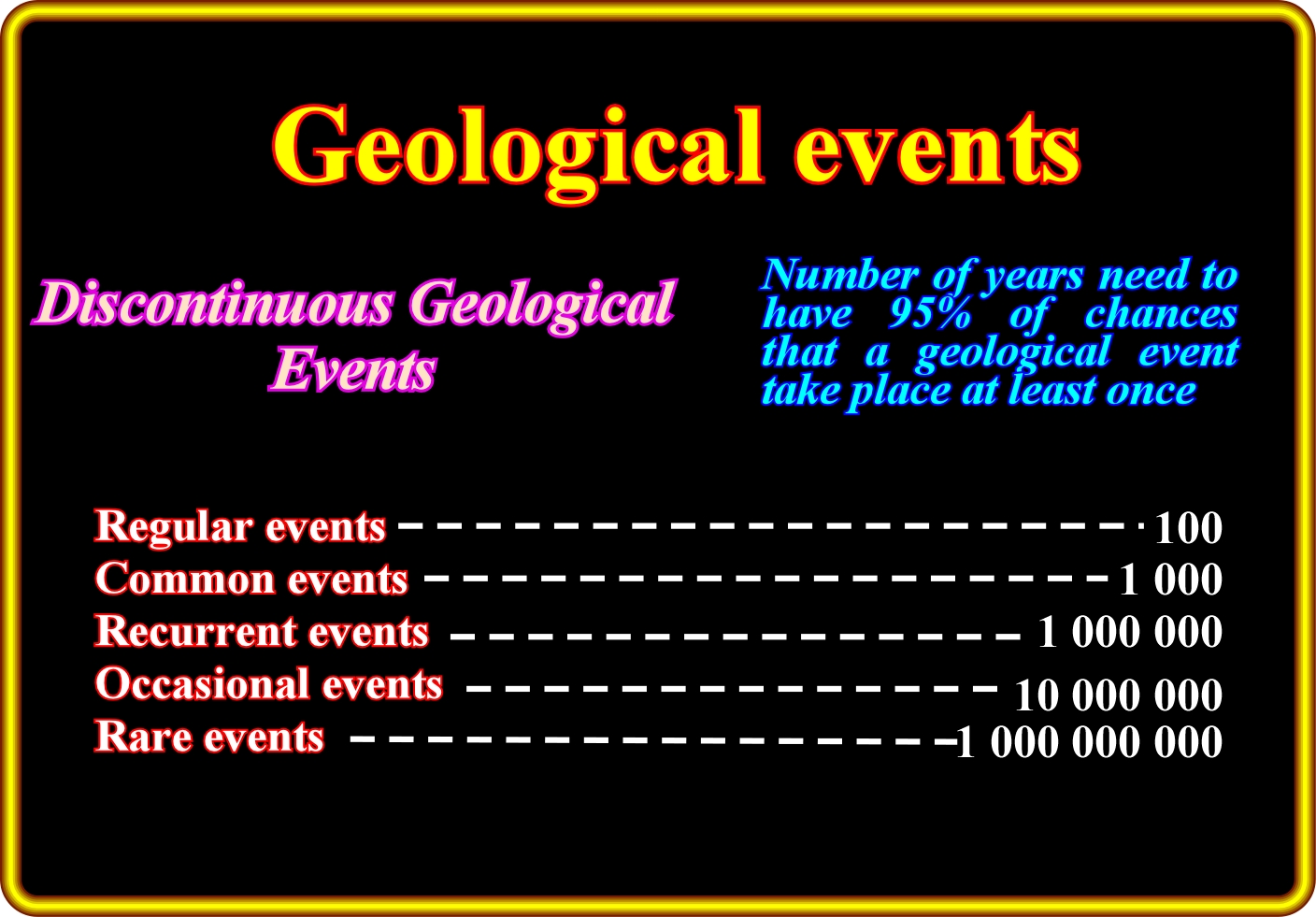

According to its frequency, Gretener (1967) classified a geological event in : (i) Regular, which takes place, more or less, every 100 year ; (ii) Common, which occurs, more or less, every 1000 years ; (iii) Recurrent, which happens, more or less, every 1 000 000 years ; (iv) Occasional, which comes about, more or less, every 10 000 000 years and (v) Rare, when it occurs, more or less, every 1 000 000 000 years.

At the human scale, i.e., two or three generations, low probable geological events are considered as possible, even if there is any natural law forbidding them. In the same way, there is any law forbidding that if you throw eight dice you get eight six. It is just a question of scale. Geoscientists know that what, at the human scale, is considered impossible it is only improbable at geological scale (condition sina qua non to understand geological systems). Using a dice metaphor :

If you consider that every six of a die represents a geological agent, such a storm, hurricane, earthquake, turbidite current, etc., you can make the hypothesis that a result of 7 six (throwing eight dice) represents an event less dramatic that the one produced by a result of 8 six. Also, a result of 5 six will be even less dramatic and more frequent than a result of 7 sic, etc.

It was using such reasoning that Gretener proposed a classification for discontinuous geological events (illustrated above). Taking into account such a classification, in geological history, two families of geological events can be proposed :

i) Frequent events

Which take place at least once all 100 My. Their time-duration is around 1 My (1/100 of total time).

ii) Rare events

Which take place at least once all 1 000 My. Their time-duration is about 10 My.

In this sense a turbidite current (gravity current in a sensu lato) is a regular or common geological event. In a particular basin, its occurrence-time ranges between 1 and 5 000 years. In other words, in any way, a turbidite current can be taken as a rare geological event, that is to say, as a punctual geological episode with a low rate of renewal in the Earth’s history (2-5 times). On the other hand, it must be notice that an instantaneous geological event, as a turbidite current, is a relative concept. In fact, taking into account the deep geological-time, the time-duration of a geological event is always a relative concept.

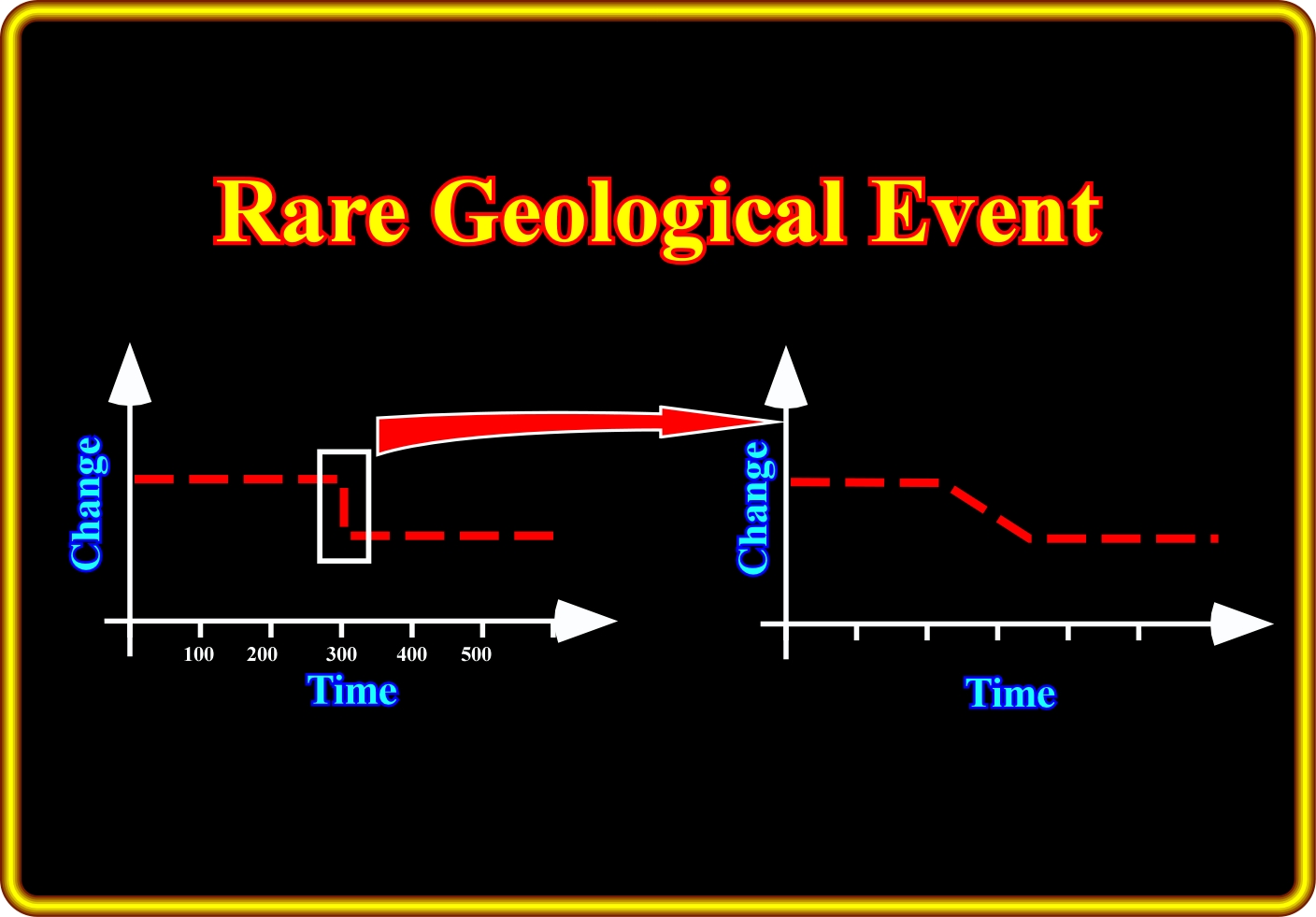

Mathematically, an instantaneous event is characterized by a time-duration exceeding barely 1/100 of total-time. Such a concept, when expressed diagrammatically (change versus time), as depicted on the plate below, the changing-time corresponds just to the thickness of the pencil line. Knowing the time-duration of the geological events and the directly or indirectly associated deposits, geoscientists must, always, take into account the completeness and preservation of sedimentary records. On this subject, the completeness and preservation of turbidite deposits are quite important to the understanding of turbidite depositional systems.

At geological scale (on the left of this plate), a Paleozoic geological event, such a stratigraphic sequence-cycle (induced by a 3rd order eustatic cycle, which time-duration ranges between 0.5 and 3 My) is an instantaneous geological event. Its time-duration (3-5 My) is approximately 1/100 of the total-time of the Phanerozoic. However, in a dilated time-scale (on the right), the same event has a finite time-duration of 6 My. All this is quite important to understand the philosophy of the Sequential-Stratigraphy, in which the building block (stratigraphic sequence-cycle) is an instantaneous stratigraphic event. In other words, if the effective deposition-time (deposition time of the basin floor fan + slope fan + lowstand prograding wedge + transgressive systems tract + highstand systems tract) of a sequence-cycle is, let's say, 500 years and the total-time (time-difference between the two unconformities bounding the sequence-cycle) is 3-5 millions years (more or less the age of the Humanity), one can say, that during the deposition of a cycle-sequence most of the time nothing happens. As a famous geoscientist said, Geology is like an Emmenthal cheese (characterised by large holes, the "eyes" created by CO2 bubbles) there are more holes (nothing happens) that cheese (something happens).